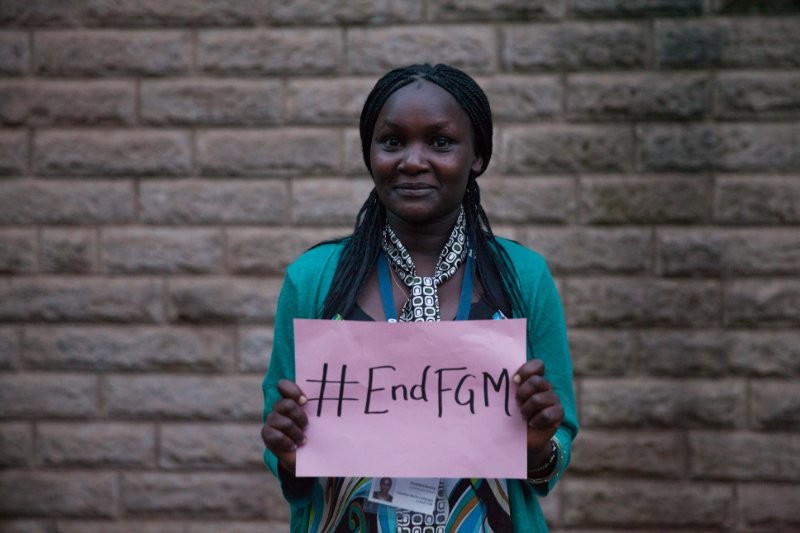

Our co-founder Domtila Chesang is a prominent women’s rights activist and Queen’s Young Leaders award recipient in 2017.

Our co-founder Domtila Chesang is a prominent women’s rights activist and Queen’s Young Leaders award recipient in 2017.

We recently sat down with our co-founder and Kenya representative Domtila Chesang, who is a human rights activist known for her grassroots campaigns against female genital mutilation (FGM) and gender-based violence. She is also the founder and director of Kenya-based I_Rep Foundation, which is established to address various forms of violence against girls and women by engaging various members of the community, including men and religious leaders. Chesang was born and raised in West Pokot County, where FGM is widely practiced.

Here’s what she had to say:

Q: You’ve been in this work for 9 years, so you have extensive experience. What are some of the challenges you’ve faced as a campaigner working to end FGM and child marriage in Kenya?

ITS HARD WORK! Working as a frontline grassroots campaigner for over 9 years advocating for the elimination of harmful cultural practices has taught me a number of lessons. First the work itself calls for a lot of sacrifice and selflessness. You have to put other people first and you come second however much you know that shouldn’t be the case. You experience several moments of burn outs and still you don’t give up because you signed up for it. Sometimes I don’t know how to do anything else or what is going on outside the FGM space. Your life revolves around it. But only now, I am slowly learning to prioritize my own family and kids.

I’ve even had nightmares where I have more than once dreamt that I was forcefully held and cut. It’s only the people who have been there and those who truly care who will understand what it means for frontline activists to put their lives out there — sometimes at risk and to always work under pressure. I also learned it is totally different to work from Nairobi than to work from West Pokot on the same course. As a community activist, it means you are constantly in contact with everyone in the space, activists, victims, survivors, police, the local administration, the community and so on and forth. You are not working with people remotely but physical interactions that makes it hard to separate your life and your job.

Q: In Kenya, each region is different. What is unique to your home region or the regions you’ve primarily worked in?

A: My community is very unique in the sense that we are mostly known as the county that is not safe due to insecurities issues caused as a result of intertribal conflicts among bordering communities. The media has made it clear for everyone that West Pokot County is a no-go zone. We are therefore known to be an unfriendly community which is not true. This portrayed media picture has made the county to be left out and miss out on most donor and partnership investments. Not many people know that the Pokot Community practice type three of FGM, which is considered the most severe type. Most communities in Kenya practice type two and one of FGM.

My county is also very complicated and difficult to navigate due to its hilly terrain, characterized by poor road network and limited connectivity. It can take you a whole day or so to make it to a village either by motorcycle or by foot because the roads are impassible. My community is also among the leading in illiteracy with 67% illiteracy levels and high level of poverty due to the fact that most parts of the land is semi-arid and dry which receives minimal rainfall. Most of the population here are pastoralists and nomads. The Pokots are very friendly and very receptive. FGM is embed in cultural belief that states that a girl can only transition to womanhood through the cut (rite of passage). However, with the right support and approach this rite, which is actually torture, is easily breakable.

A girl can be safe from FGM but still fall a victim of child marriage, drop out of school, be subjected to stigma, be a victim of gender-based violence and economic and social gender-based violence. FGM requires holistic approach by both campaigners, donors and governments. Policies and laws are number one priority in ending violence against women and girls. Investment in campaigns that are geared towards the girl/women empowerment as a whole should be encouraged not just FGM alone. Girls needs sustainable protection, they need education, they require medical support and psychosocial support.

In short, the community must be supported towards providing a more sustainable and conducive environment for girls to thrive.

Q: How can some of the lessons you’ve learned apply to help young End FGM activists in countries like Egypt, Gambia, or Sierra Leone (where FGM isn’t even banned yet by law)?

A: Strategy is key. Have a clear strategy of what you want to achieve and stick to a plan, lest you get tossed in all directions and in the process, you burn out and can’t trace impact of all the efforts you have put in the work. You must have a clear roadmap that can guide you and keep you on track so that you can avoid distractions. Have a clear goal for everything you do. Monitor and evaluate the work to inform your end goal. Make sure you are informed of all the existing structures and support systems that are there to back you up if the law is not yet in existence.

Once you dive into this work there’s no going back. It can even cost you your life, so you must ensure you are really committed to this and you are not driven by anything apart from your passion to create a just society for girls/women. Consistency is key. The amount of work you do in a day is not the deal but how many times you do it in a year matters. It takes time, patience, tolerance and perseverance. Stay on the course whether the money is there or not.

It’s important to note that there’s need to really find ways of working closely with the government and other influencers to push for laws and policies. There’s power in collaboration.

Q: When girls are able to escape child marriage safely, FGM, and other harmful practices, what resources could they benefit from? Just because a girl escapes, doesn’t mean she’s safe, sadly. How can we sustain their well-being?

A: First, is to create a strong and functioning referral pathway from the community level to the top high, for identification, reporting, rescue and also for follow-up support. The lack of information and existing gaps in reporting and rescue makes it difficult to identify girls at risk, to rescue them and to offer support they need.

There’s need to create and provide resources for the girl child as she grows up, because nobody prepares her for the cut until it is her time. I used to really look forward to the time I would be cut because I thought it was fun, gifts, merry and everything else that is good just as all young girls are deceived before their time. I didn’t know that there was more to FGM than that. I knew it only that one morning when I saw my cousin being pinned down and all her genitals chopped off.

There’s a need to develop training and support for girls who have escaped these vices, to help them overcome that trauma and most importantly stigma of not looking like the others. These could be in the form of books, radio programs, TV programs, classes, capacity-building at available institutions like churches, mosques, and schools. There must be at least recovery centers for victims of stigma and such like incidences. The need to make sure girls are in school is another psychosocial support that guarantees the future of a girl.

Q: Activism is a tough space, especially in this line of work. What activities do you take part in to maintain your own mental health and well-being?

A: I have built a strong support system both locally and internationally of women and sisters doing similar work and those who understand my work. Whenever am down or low I reach out and vent without being judged. I reach out and speak, and the other person on the other end listens and supports. I also listen to gospel music, go for a drive with loud music or just do whatever else makes me happy like hang out with friends. I dress nice and admire myself in the mirror – sounds funny, but it works.

I also count all the good things I have done and celebrate that. This has taken time to really master how to survive and honestly there’s no manual you just got to focus on what makes you happy at that moment.

Q: What is unique about AWRA’s vision in sustaining a better reality for future generations?

A: AWRA is a solution to most if not all the gaps I have sited in my writing. AWRA seeks to provide resources and support for all advocates promoting the rights of women and girls. It provides guidelines and information that can inform other advocates and upcoming campaigners what to watch out for — tested and proven approaches in ending FGM. AWRA also supports to bridge the gap between activists and donors, government and other private entities by providing skills and knowledge that is required to bring about sustainable change. We are capable of providing capacity-building that I mentioned above to not only prevent FGM, but help girls and women who escape such vices.

Activists on their own might not be able to lobby the government to make laws and policies to ban these vices and protect girls but AWRA is that platform where voices are connected and efforts harnessed to lobby for global action to happen. AWRA is the voice of action at a higher level where campaigners feel limited.

But, there is very limited funding and resources available especially for frontline and grassroots activists and organizations. The solution to this is for funders to provide grassroots organization like AWRA with support to grow their capacity so that they can be able to employ professional to do the technical work and the activists can work on eradicating the harmful practices. This way we will be spending more of our time working on the strategies to end FGM and other practices — and not struggling to fundraise. We must decolonize the funding space.

Ending Female Genital Mutilation in Africa Requires a Holistic Approach. Here’s Why.

Our co-founder Domtila Chesang is a prominent women’s rights activist and Queen’s Young Leaders award recipient in 2017.

We recently sat down with our co-founder and Kenya representative Domtila Chesang, who is a human rights activist known for her grassroots campaigns against female genital mutilation (FGM) and gender-based violence. She is also the founder and director of Kenya-based I_Rep Foundation, which is established to address various forms of violence against girls and women by engaging various members of the community, including men and religious leaders. Chesang was born and raised in West Pokot County, where FGM is widely practiced.

Here’s what she had to say:

Q: You’ve been in this work for 9 years, so you have extensive experience. What are some of the challenges you’ve faced as a campaigner working to end FGM and child marriage in Kenya?

ITS HARD WORK! Working as a frontline grassroots campaigner for over 9 years advocating for the elimination of harmful cultural practices has taught me a number of lessons. First the work itself calls for a lot of sacrifice and selflessness. You have to put other people first and you come second however much you know that shouldn’t be the case. You experience several moments of burn outs and still you don’t give up because you signed up for it. Sometimes I don’t know how to do anything else or what is going on outside the FGM space. Your life revolves around it. But only now, I am slowly learning to prioritize my own family and kids.

I’ve even had nightmares where I have more than once dreamt that I was forcefully held and cut. It’s only the people who have been there and those who truly care who will understand what it means for frontline activists to put their lives out there — sometimes at risk and to always work under pressure. I also learned it is totally different to work from Nairobi than to work from West Pokot on the same course. As a community activist, it means you are constantly in contact with everyone in the space, activists, victims, survivors, police, the local administration, the community and so on and forth. You are not working with people remotely but physical interactions that makes it hard to separate your life and your job.

Q: In Kenya, each region is different. What is unique to your home region or the regions you’ve primarily worked in?

A: My community is very unique in the sense that we are mostly known as the county that is not safe due to insecurities issues caused as a result of intertribal conflicts among bordering communities. The media has made it clear for everyone that West Pokot County is a no-go zone. We are therefore known to be an unfriendly community which is not true. This portrayed media picture has made the county to be left out and miss out on most donor and partnership investments. Not many people know that the Pokot Community practice type three of FGM, which is considered the most severe type. Most communities in Kenya practice type two and one of FGM.

My county is also very complicated and difficult to navigate due to its hilly terrain, characterized by poor road network and limited connectivity. It can take you a whole day or so to make it to a village either by motorcycle or by foot because the roads are impassible. My community is also among the leading in illiteracy with 67% illiteracy levels and high level of poverty due to the fact that most parts of the land is semi-arid and dry which receives minimal rainfall. Most of the population here are pastoralists and nomads. The Pokots are very friendly and very receptive. FGM is embed in cultural belief that states that a girl can only transition to womanhood through the cut (rite of passage). However, with the right support and approach this rite, which is actually torture, is easily breakable.

A girl can be safe from FGM but still fall a victim of child marriage, drop out of school, be subjected to stigma, be a victim of gender-based violence and economic and social gender-based violence. FGM requires holistic approach by both campaigners, donors and governments. Policies and laws are number one priority in ending violence against women and girls. Investment in campaigns that are geared towards the girl/women empowerment as a whole should be encouraged not just FGM alone. Girls needs sustainable protection, they need education, they require medical support and psychosocial support.

In short, the community must be supported towards providing a more sustainable and conducive environment for girls to thrive.

Q: How can some of the lessons you’ve learned apply to help young End FGM activists in countries like Egypt, Gambia, or Sierra Leone (where FGM isn’t even banned yet by law)?

A: Strategy is key. Have a clear strategy of what you want to achieve and stick to a plan, lest you get tossed in all directions and in the process, you burn out and can’t trace impact of all the efforts you have put in the work. You must have a clear roadmap that can guide you and keep you on track so that you can avoid distractions. Have a clear goal for everything you do. Monitor and evaluate the work to inform your end goal. Make sure you are informed of all the existing structures and support systems that are there to back you up if the law is not yet in existence.

Once you dive into this work there’s no going back. It can even cost you your life, so you must ensure you are really committed to this and you are not driven by anything apart from your passion to create a just society for girls/women. Consistency is key. The amount of work you do in a day is not the deal but how many times you do it in a year matters. It takes time, patience, tolerance and perseverance. Stay on the course whether the money is there or not.

It’s important to note that there’s need to really find ways of working closely with the government and other influencers to push for laws and policies. There’s power in collaboration.

Q: When girls are able to escape child marriage safely, FGM, and other harmful practices, what resources could they benefit from? Just because a girl escapes, doesn’t mean she’s safe, sadly. How can we sustain their well-being?

A: First, is to create a strong and functioning referral pathway from the community level to the top high, for identification, reporting, rescue and also for follow-up support. The lack of information and existing gaps in reporting and rescue makes it difficult to identify girls at risk, to rescue them and to offer support they need.

There’s need to create and provide resources for the girl child as she grows up, because nobody prepares her for the cut until it is her time. I used to really look forward to the time I would be cut because I thought it was fun, gifts, merry and everything else that is good just as all young girls are deceived before their time. I didn’t know that there was more to FGM than that. I knew it only that one morning when I saw my cousin being pinned down and all her genitals chopped off.

There’s a need to develop training and support for girls who have escaped these vices, to help them overcome that trauma and most importantly stigma of not looking like the others. These could be in the form of books, radio programs, TV programs, classes, capacity-building at available institutions like churches, mosques, and schools. There must be at least recovery centers for victims of stigma and such like incidences. The need to make sure girls are in school is another psychosocial support that guarantees the future of a girl.

Q: Activism is a tough space, especially in this line of work. What activities do you take part in to maintain your own mental health and well-being?

A: I have built a strong support system both locally and internationally of women and sisters doing similar work and those who understand my work. Whenever am down or low I reach out and vent without being judged. I reach out and speak, and the other person on the other end listens and supports. I also listen to gospel music, go for a drive with loud music or just do whatever else makes me happy like hang out with friends. I dress nice and admire myself in the mirror – sounds funny, but it works.

I also count all the good things I have done and celebrate that. This has taken time to really master how to survive and honestly there’s no manual you just got to focus on what makes you happy at that moment.

Q: What is unique about AWRA’s vision in sustaining a better reality for future generations?

A: AWRA is a solution to most if not all the gaps I have sited in my writing. AWRA seeks to provide resources and support for all advocates promoting the rights of women and girls. It provides guidelines and information that can inform other advocates and upcoming campaigners what to watch out for — tested and proven approaches in ending FGM. AWRA also supports to bridge the gap between activists and donors, government and other private entities by providing skills and knowledge that is required to bring about sustainable change. We are capable of providing capacity-building that I mentioned above to not only prevent FGM, but help girls and women who escape such vices.

Activists on their own might not be able to lobby the government to make laws and policies to ban these vices and protect girls but AWRA is that platform where voices are connected and efforts harnessed to lobby for global action to happen. AWRA is the voice of action at a higher level where campaigners feel limited.

But, there is very limited funding and resources available especially for frontline and grassroots activists and organizations. The solution to this is for funders to provide grassroots organization like AWRA with support to grow their capacity so that they can be able to employ professional to do the technical work and the activists can work on eradicating the harmful practices. This way we will be spending more of our time working on the strategies to end FGM and other practices — and not struggling to fundraise. We must decolonize the funding space.